Christian Prager

University of Bonn

Maya Writing between Tradition and Innovation: Diachronic and Synchronous Approaches to Understanding Graphemic and Graphetic Principles in a Two-Thousand-Year History of Writing in the Americas

Abstract

Maya script consists of about 800 iconic morphographs and syllabic signs, known from thousands of inscription-bearing objects that come from around 550 sites and span dates between around 500 BC. to 1500 AD. The language of the hieroglyphs is called Classic Mayan and has been preserved in varying degrees in the colonial and recent Ch'olan and Yucatecan languages. Most of the texts contain calendric information that date events down to precise days and thus provide unique data on the history of writing and language, which can then be very precisely reconstructed and compared with the findings made by historical linguistics. All more than 12.000 inscriptions were created around the palaces of kings, who ruled over independent city-states that were extended across the territories of present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and Honduras.

The hieroglyphic writing system, which had remained only partially deciphered until a few decades ago, belongs to one of the most significant writing traditions of the ancient world. In contrast with Egyptian or Mesopotamian writing traditions, the great challenge facing Maya writing projects is that only some 70% of all signs for words and syllables have been securely deciphered to date. Today, in addition to the principle of rendering words using logographic or phonetic signs or combining both, we are aware of a wide range of writing and layout principles, through which not only individual graphemes, but also words of Classic Mayan could be written using a great number of variants. Scribes aspired to achieve the utmost visual splendour and optical variation and it is possible that, alongside the well-known graphic and artistic horror vacui, there was also a horror repetitionis. Probable reasons for this may be that, apart from the contents of the text, both the high aesthetic quality of the whole work and the individual skills of its creator should aim to impress the viewer’s eye: To the present-day viewer of hieroglyphic texts, it would seem that monotony, conformity, and repetition were to be avoided; calligraphic variety determined the work of a writer or his workshop.

In laying out a text and its individual graphemes, scribes had to pay attention not only to the nature and form of the text-carrying material, but also to the space available to them for the image program and the text. They considered both aesthetics and writing economics making use of a palette of graphotactic and formal layout possibilities. Master scribes, in order to avoid displeasing repetitions in a text, in addition to the principle of pars pro toto writing of full variants, also used graphic allomorphy and took into account principles of homophony, polyphony, and complex groups of signs in order to produce calligraphically differentiated texts. Abbreviations or short versions of full variants arose particularly in the context of ligature and infixation, i.e. through the interference of several graphemes in a single hieroglyphic block. This graphetic phenomenon is referred to as overlapping or superimposition; it results from the complete or partial superimposition of two or more signs, in which the elements that are covered remain only partially visible (pars pro toto), but are understood as previously independent graphemes. One should not forget the existence of writing strategies based on the different functions of signs, through which words are formed using either only word signs or only syllabic signs, as well as a combination of word and syllabic signs, or with the help of diacritical signs. Once again, the full repertoire of calligraphic usages came into play.

In my contribution, I would like to examine these graphemic and graphetic principles diachronically and pursue the question of whether these are principles that can already be found in the earliest texts of the Maya or at what point in time they first appeared as innovations and were used consistently in the scriptural tradition. Questions: Are the above-mentioned graphetic and graphemic phenomena cumulative, widespread in time and space, or are they regional and temporally limited phenomena in the history of writing.

Images Related to the Talk

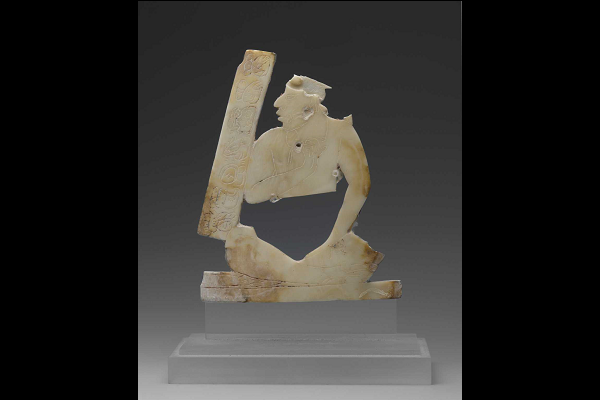

17513

17623

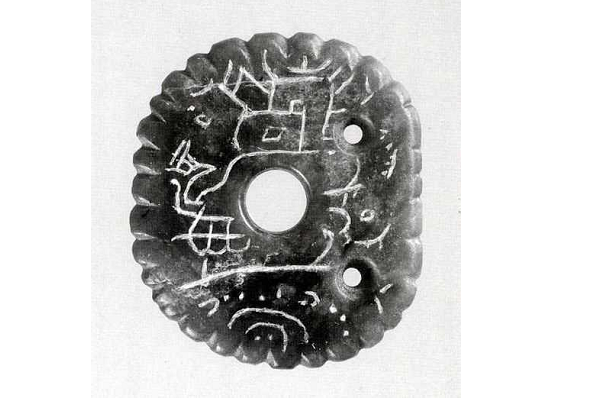

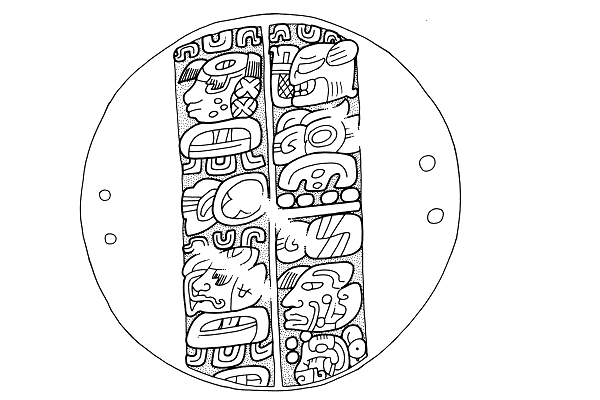

La Fortuna slate disk